APRIL 15TH, 2015

Master & Lingo: Conversations on Skype and Gmail

BY MAREN MILLER AND SAKI SATO

We interviewed each other about the work in our show Master & Lingo at Good Work Gallery. Here are our thoughts on art and various other subjects.

Design vs. Image / Pattern vs. Image / Decoration vs. Image

MM: Want look at some of these questions I e-mailed you? “When you’re drawing, do you make a distinction between designs and images?”

SS: Oh yeah, I wasn’t totally sure what you meant with that one. Instead of “design” vs “image”, I sort of thought about patterns instead. I was ordering samples to make wallpaper. And it was cool to think about making wallpaper because I was thinking: “Oh! I’d like to incorporate my objects [from the show]… but I have to put them in a repeatable pattern.” And that was kind of weird, because it made me wonder about what is “pattern” vs. “image”. That’s how I took your question.

[A Pattern] doesn’t usually have a message. It’ll be a collection of objects but it won’t really make you question each object in the pattern. “Oh, cute, it’s there,” you might think. You don’t really ask: “What is this corvette doing next to this motorcycle on these pajamas?” It’s not confusing, you just take it at face value.

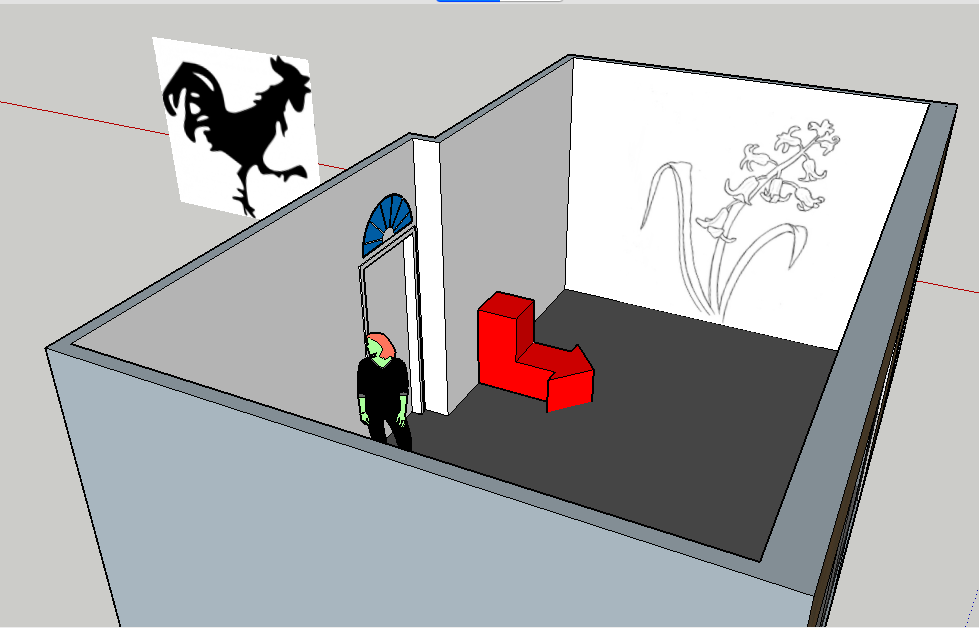

MM: I think I asked that question because when we were planning the show we talked about putting an image on the far wall by the door. We talked about using a flower or a rooster…and you didn’t really care what the image was.

SS: [Laughing] I know you were like, “Saki… What? Why?” And I kept saying, “No, stay with me, I just have a good feeling about the flower, Maren.”

MM: It was cool! I’m interested in this decorative image [you wanted to put on the wall] that was important to the show but not necessarily a piece…

SS: Yeah, the weird thing about that one… I guess it was like— you’re right— maybe purely decorative. I wasn’t interested in what it meant. I wanted it to be a statement that would create an air of… 1) “Larger than life,” and 2) “In your face,” so you’d enter the show and be like, “Whoa. What is this? Big flower.”

But we didn’t do that! it would’ve been kinda weird and funny.

Friendly Objects / Decorative Patterns, Meaningful Images

SS: Also, I was thinking about my objects, and how I like to try and make them the least specific I can. I mean, they are really specific but then I round the corners and solid out the colors— try to make them the most general I can. But they’re not generic, they still have character…

MM: They’re friendly.

SS: Yeah! And “friendly” glosses over a lot of things. Like a pattern. I guess i’m kinda thinking of the tension between “pattern,” which I see as a pleasing image, and “image,” which is like… presenting a meaning or asking questions about the significance of some juxtaposition. To me, pattern is just aesthetic juxtaposition.

MM: It seems like you’re interested in that moment of pushing the viewer to ask a question— Ok, so, you wouldn’t question the pajamas but…

[in unison]: Why not?

SS: Yeah, right? Maybe it’s the repetition… maybe it loses its meaning. And I was thinking, “If I do that with my things, what would they turn into?” Because so far nothing repeats. Each object is unique, and one is next to the other for a specific reason. Even though the reason is sometimes purely aesthetic.

MM: If you step back even further from the specificity of pattern, there’s the question of where to draw the line between an “aesthetic” decision and a “meaning” decision.

SS: On the one hand, there’s the scene that an image presents us. And you’re thinking: “Yeah…why IS that puppy looking away from us? Is he sad? Is he being abused? Is he happy to be looking out the window?” But like if you saw a pattern of puppies…I dunno. You might not think twice about what the puppies are thinking.

MM: It’s funny that you are talking about it only in terms of pattern. Could you also just use the word “decorative” ?

SS: That’s true. I guess I was thinking in terms of pattern because I wanted to make that wallpaper. But in terms of wanting to put that flower on the wall and it meaning basically nothing… that would be decorative.

I guess it’s more like emotional meaning. It’s more raw. It feels good. It’s like, aesthetically: “Yes.”

[MM laughs]

SS: It all comes back to that flower! [Laughing] I guess that’s the feeling I was having. And I couldn’t explain it to you at the time. All I could say was, “Flower, Maren. Flower!”

Maren Talks About Painting / Plato’s Theory of Forms

SS: What do you feel about “aesthetic” objects, like, curtains and rugs? People surround themselves with those objects because they feel nice. Or they’re useful. We need them, too.

MM: I think it’s a combination of things. First of all, I got really interested in objects that are almost two-dimensional. How a rug is…

SS: Literally flat.

MM: You can think of it as a pattern that goes directly into your house. Decoration. Or you can think of it as something physical, that you can stand on, that has a relationship to your body.

Same goes with the curtain. Though I think the curtain is a little bit more loaded [with meaning] for me just because it’s also fabric— like a painting is fabric— and you hang it on the wall or in front of something.

SS: I’m feeling you. They lend themselves to flat images well. They’re already pretty flat objects.

MM: It’s also partly because I was trying to make paintings for a long time and I was never able to do it on stretched canvas. All the paintings I’d make would be on panels. They felt to me like little tiles, or a physical panel. And then I also got interested in going the other direction too: painting directly on the canvas. Cutting it out and treating it like a piece of fabric when I put it on the wall. In the same way as I was considering the sides of the panels and how they were painted and how thick it was.

Master & Lingo

SS: You’re turning a painting into an object. And then I’m trying to take an object and turn it into an image. You’re trying to make the 2D painting into a 3D object and I’m making the 3D object into a 2D image. We’re going back and forth in this world.

MM: But really, I think that neither of us are particularly attached to the final product of our sculptures. If something happened to my plinth I would just make another one. It wouldn’t be a big deal.

It seems like the same thing for your work. I think that has to do with being really interested in trying to translate what it means to be thinking or describing the experience of an image, rather than actually creating it.

SS: This makes me think of… I mean, I never looked into it that much and I don’t plan to because I like thinking about it how I want to think about it… but, Plato’s Theory of Forms.

MM: Yeah! I always think about that when I look at your work.

SS: I don’t know what he says in depth. But the gist of it, well… he applied it to geometry. Geometric shapes are perfect and they live in an ideal world and any material representation of them is just a copy. So we always know: “Ok we have this thing in reality but it actually lives in our minds.”

MM: And I feel like that’s really dependent on language and how we’ve been taught to talk about the world. That’s another reason that I like incorporating directional representations into my work. Cuz that feeling points to language in an interesting way, and how we understand space without a specific text.

SS: You’re taking an arrow, which is an image, but has language embedded in it. An image language, a universal language: it tells you where to go… You don’t need to know the word for what it’s trying to tell you. But its the language of directing you to things or conveying meaning at a very basic level.

Language of Symbols

MM: The arrow chair wasn’t totally successful because I didn’t want to have to ask people to sit in it. But I wanted them to know it was a chair. Reminding you that it’s an object in a space. It relates to your body but doesn’t necessarily have to be about you directly experiencing it.

SS: It’s like you’re making use of the object. Normally it’s a symbol that you follow.

You have an object that exists in this world of symbols…the arrow meaning: “Go here.” You can never make it real… when you make a real arrow it’s always still a picture, it’s always an image. It’s never really an object, but in this case you’re making it an object you can use.

MM: But I also really like that moment of the actual object being really dumb. I wanted to conjure this image of sitting on it and then there being a big arrow between your legs.

SS: It’s like you’re degrading the arrow because it’s this universal symbol that you’re sitting on… but it’s also degrading you. By making fun of you.

MM: [Laughing] When I sent a picture of the sculpture to [our friend] Katya she kept texting me these phrases like: “The answer was sitting right in front of me!” I really liked that.

SS: Oh shit the neighbor’s cat! Chip come here I wanna show you to Maren!

MM: Awwwwwww

SS: His name is Chips. He doesn’t like being held. His name is the plural of Chip. Chips.

MM: Cool! Multiple Chips!

SS: So cute.

MM: So cute.

SS: So. We’re talking about the answer. That answer underneath you.

MM: The answer sitting right in front of you.

SS: We need to caption your sculpture with that some day.

MM: I like that… actualizing language into a sort of dumb object. That’s definitely something I was thinking about when I made that labyrinth pillow a while ago.

MM: The labyrinth has a really specific relationship to your body. Because you’re supposed to…

SS: To walk it.

MM: Yes. Historically, it’s this thing that you walk, this meditative moment. But zoomed out it’s no longer something your body can directly relate to. Then I put it on the pillow. And pillow is something that your body really has one really specific relationship to.

SS: Point of contact.

MM: Yeah. And it’s pointing to a different use of space. I was thinking about that with the arrow chair.

SS: Wait…so…I really like that. Labyrinth on a pillow. Rug on a rock. Curtain on the plinth. I really like thinking about your things-on-things. Objects within objects.

MM: The plinth was something different…I’ve done a lot with the curtain hanging off the wall… but that came out from the wall…still figuring that out…

SS: Yeah! I guess it literally came out from the wall. Cuz you have the shadow – but it’s almost like you pulled it out of the wall. That’s the path it followed. And if you look at it head-on…well, it’s parallel to the wall.

SS: By the way… see something?? [shows Maren her old painting hanging on the wall]

MM: OOoooh! I do!

SS: Taylor helped me finally put up your thing!

MM: Cool!

SS: That one’s kind of a curtain.

Trompe-L’oeil

SS: Oh, and kind of unrelated, going back to something I mentioned in our email. Did you like the thing I told you about the gift shop that had the painted rugs on the floor?

MM: Yeah that sounds so nice.

SS: They were really tender, delicate green and white checkered with little roses…and then they wore down over the years as people walked on them. It made me realize they don’t need real rugs. They’d just get dirty. They need them for decoration— why not just paint ‘em on the floor.

This makes me think… is what we’re doing something like trompe-l’oeil? Does it relate to that? Or maybe… not like the trompe-l’oeil part of wanting to make it look so real that you’re tricked— because my objects don’t look real. But I want to make my objects so… I don’t know, so joyful that you don’t want the real thing.

For example, you put an urn on your shelf. The urn is a container, a vessel— made to hold liquid or something, but mostly your just want to have it on display. In this case, a picture of an urn would be just as good, or even better than the real thing. A picture would be less fragile.

What I want… is to give the image-objects I make their own utility, or value. The mirror I made may never be able to be useful as a reflecting surface, but it still brings me… “joy” with its pleasing shape and pretty colors, and the feel I get when I hold it in my hand. So, to me, it’s already halfway there. A decorative hand mirror is definitely useful for its aesthetic qualities.

MM: Yeah it’s sort of like trying to experiment with making something into a symbol. I don’t know if that’s the right word.

SS: I guess i’m thinking about relation to objects. Like: what if we made all of our arrows so comfortable?

MM: [Laughing] The only thing that works in that same way for most people— automatically— are… ubiquitous symbols that are loaded with a ton of meaning. Like a cross.

People treat the image of a cross and an actual cross in a very similar way.

On the other end of the spectrum, people usually treat an arrow the same way, whether it’s cut out of something or drawn onto a piece of paper.

SS: It doesn’t matter if it’s 2D or 3D.

MM: It’s not dependent on its’ material. And that’s an interesting place.

SS: I was thinking about… I guess you could call them super-universal or transcendental symbols [like arrows], and then I guess you have the ones that are more…generic or secular [like food staples]. And then the ones that are so heavy with meaning— like the cross— those are the ones I don’t think I can use in my work. At least not for this show.

MM: [Referring to the email:] I love the thing you wrote about the banana.

SS: Yeah, I was thinking about that…I want to create an effect that… for example, if I present you with a banana, it is so universal, so generic, that you can’t really make a value judgement about it right away. Because when I show it to you there’s so little context that you can’t take it personally.

If I show you a picture of a banana you won’t be say, “Oh nooo… I hate bananas.”

You don’t feel like I’m asking you if you like bananas, or what you think about bananas. It kind of just represents fruit in general. Maybe an apple would do the same. But an apple has more historical baggage attached… Well so do bananas… but I don’t know that you could say one piece of its history defines its overall meaning. It’s still just a simple piece of food that babies, children and adults eat every day.

I mean, you can always put meaning on to something, but I like the objects that you’d be presented with and would have a neutral response. “Oh. Banana. Wonder what’s next?”

MM: Yeah.

SS: The opposite of that is showing someone a cross: “Oh, CROSS. I know this.”

You have an opinion about it. Feel the history.

But what if I took a banana and put it next to the cross? What would you think?

I like that because it’s taking something really neutral and something really heavy but nullifying the heavy meaning in a way because I have no idea what banana and cross ever had to do with each other. So it’s kind of liberating. It’s like I’m telling you there’s a story, but really there is no story. So you go to this dead end where you’re like, “Ok. I don’t get it.”

But it’s liberating for me to feel like I don’t get it.

Usually when I see a cross I say, “I know this. I get it,” and that kills any imaginative momentum.

MM: That’s super interesting about the moment of feeling liberated when you don’t get it.

There’s this thing that people often say to me: It looks like this is from a play. or it looks like a prop. or what world is this from?

And it always kind of bums me out when people say that because I don’t want people to look at my work and ask “What am I missing?” I want them to feel good in that moment of this thing being in your space.

SS: I know what you mean! I think props are an easy way to understand things as outside of our reality but belonging somewhere near our universe.

MM: We like working with things that are familiar and the kinds of emotions that that brings up. But I also feel that in a lot of ways we’re trying to isolate that feeling.

SS: And I wish the people who saw our work were like… “It’s ok that I don’t get it. It takes me to a new place where I can make up anything I want about it…”

But, yeah, I guess that’s the goal. I don’t know if it’ll get easier or harder… I’m sure people will always look for a specific predetermined meaning that’s easy to digest. It’s hard to describe trying to look for a way to take away something’s everyday meaning and make a new one. Cuz you’re in the space with the thing, but not in the way you’d normally be with it. Like being in the space with a curtain on a plinth… how do you relate to curtains there? And when you go home you hopefully relate to curtains in a new way.

Art That Touches You / Touching Public Sculpture

SS: Ok, so we talked about ideal objects in an ideal dimension before… but it made me think about how I really like that movie “Who Framed Roger Rabbit?” You know, cartoons in our reality, mixing the real with the artificial…

Did you have another thing you grew up with that really influenced you?

MM: Well, that scene in Beetlejuice where the sculptures came alive grab people always just blew my mind. I was obsessed with it.

SS: You just wanna touch people with you work, Maren.

MM: I want people to look at it and want to touch it so badly. But I don’t want to do it in a way that’s cheap. I don’t want just make it look all squishy… I want to make people want to touch something because of the shape that it’s in.

SS: Yeah, that’s so cool… I feel you. I think we both have that— the pleasure in sculpture is handling it. And we come up against this weird thing in the art world where you’re not supposed to touch things. and it’s hard to tell people to touch things without it being so overbearing.

MM: And you also don’t want to be TOLD to touch something! That’s super annoying.

SS: I dunno what the solution is. Maybe we just need to make a new environment where it’s OK to touch things.

MM: Well, I think that’s why we’re both so interested in public sculpture.

SS: You can climb on it and it’s indestructible!

MM: That context is established. Even if it has the sign not to touch… you know people are gonna touch it.

SS: Still gonna touch! Wipe that Botero penis until it shines.

[MM laughs]

SS: So shiny.

MM: It’s just a wonderful thought.

SS: We want the art to be a more… physical, mental experience. You can get so much more out of it that way. We just need free reign. We need to make a Candy Land.

MM: The weather is less fun to deal with than people trying to touch your work.

[SS sneezes]

[MM makes a fart noise with her mouth]

SS: Ew! Don’t fart when I sneeze!

[MM makes fart noise again]

SS: That’s your response? When someone sneezes you rip a big one?

MM: Someone farted on me at the Getty today.

SS: Real close? Like, on your leg?

MM: No, SBD. It was a crowded corner of the bookstore and then suddenly I was alone with this horrible smell.

SS: They ran away?

MM: Went in there, did it, and then ran away.

SS: Taylor says it’s called crop dusting.

——————————————————— END ———————————————————